Abraham Lincoln died 151 years ago yesterday. Though he was shot on April 14, he died the following morning. Presses started rolling that day and haven’t stopped over the last century and a half. Today there are an estimated 10,000-15,000 recorded titles.

What is even more amazing is that Lincoln publishing was so immediately prolific, that lists of Lincoln-focused titles began in the same year that he died.

Last month, while Tammy and I were perusing Patten Books in St. Louis, I came across a two volume Lincoln bibliography from 1943, published by the Illinois State Historical Library that lists all known Lincoln titles (this would include printed speeches, sermons and letters) published between 1839 and 1939. Each title is numbered and placed in chronological order. There are 3,955 listed.

The list is fascinating and runs the gamut from books of value to sensationalist fluff. Some of the speeches are worth looking up. For example, I found a February 12, 1878 (Lincoln’s birthday) congressional speech listed, given by Alexander H. Stephens of Georgia. Stephens played a strange role in Lincoln’s life. They had served in Congress together and Lincoln had taken an early liking to Stephens, even saying in one of his letters that Stephens had given one of the finest speeches he had ever heard given in the House. Later, Stephens served as Vice-President in the Confederacy, inflaming northern opinions with strong pro-slavery rhetoric. Still later, he was a champion of reconciliation and a U.S. Representative. He died while in office as Georgia’s governor. So, I’m tremendously curious about his post-War comments and I’ll be looking for a copy of that in the future.

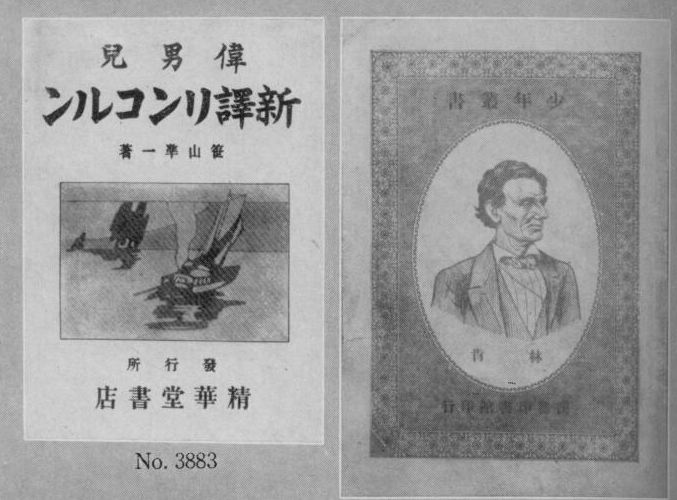

There are also foreign language titles listed, in nearly every well-used language you can imagine.

But, by far the most fascinating part of the bibliography is its introduction. It is so fascinating that I’ll just excerpt much of it, instead of paraphrasing. I hope you find this story as fun as I did. To start, you’ll need to learn a word I hadn’t encountered until this year, Lincolniana (Pronounced “Lin-coe-nee-ah-neh or “Lin coe nee A neh”).

My definition of Linconiana is “Lincoln stuff,” but the collector’s definition and the bibliographer’s definition has been honed and tweaked over time to exclude some items and include some items — mostly to weed out published items that are less relevant — or “relics” that really have tenuous ties to Lincoln. With that out of the way, let’s move over to Jay Monaghan’s Introduction to the Lincoln Bibliography.

“The first bibliography of Lincolniana appeared soon after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. In September, 1865, William V. Spencer published, as a memorial, a 346 page reprint of sermons, eulogies, and letters—material alleged to be heretofore unpublished. The compiler was a collector and his bibliography included the books and pamphlets on his own shelves.”

“The second bibliography of Lincolniana appeared in 1870—Andrew Boyd’s Memorial Lincoln Bibliography. This volume, bound in cloth, was divided into two parts, the first prepared by Charles Henry Hart, the second by Andrew Boyd….

…in the years that followed, this book became the manual for other collectors.”

“As the nineteenth century drew to a close the field of Lincolniana narrowed, relics and curios were no longer considered legitimate entries for a Lincoln bibliography. Foremost in this new trend were four collectors, Judge Daniel Fish of Minneapolis, Charles W. McLellan, who had lived in Lincoln’s Springfield, Judd Stewart of Plainfield, New Jersey, and Major William Lambert of Philadelphia….A youngster, J. B. Oakleaf of Moline, Illinois, known as “The Baby,” completed the Big Five.”

“A great friendship grew up among the Big Five. Jolly discussions of the fitness of this and that title in a collection of Lincolniana salted occasional meetings and the voluminous correspondence of the fellowship. Group opinion was the last word on what constituted Lincolniana. The Big Five possessed a “corner” in the field. Their word was law. Then one day it was discovered that another man, John E. Burton, working silently at his home in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, had built up a collection ranking with the best. From this time forward Burton had to be considered. Although he never intimately associated with the original Five, he added rules of his own to the game and set his colleagues to arguing happily over each other’s definitions of the field. “

“In 1900 Judge Fish decided to coagulate the definition of Lincolniana and at the same time list all known titles.”

“Three years later, in 1903, the Library of Congress published a check list of Lincoln books on its shelves.”

The Francis D. Tandy Company, New York, published a revised version of Daniel Fish’s bibliography in Nicolay and Hay’s twelve volume Abraham Lincoln: Complete Works. Fish listed 1,080 numbered titles. “This Lincoln Bibliography digested all previous lists and became the first standard work in the field…Fish also was the first to number the entries on his list and thus save endless identification quibbles. His bibliography became the manual by which the Big Five as well as other collectors measured their ability to acquire fugitive titles.”

“In 1908 Fish wrote a history of the Big Five entitled “Lincoln Collections and Lincoln Bibliography” in Volume III of the Bibliographical Society of America, Proceedings and Papers.

The introduction goes on to talk about what happened to each of the Big Five’s collections as they grew old and passed away. It also brings the history of Lincoln bibliography up to the then present day.

Our copy of the Illinois State Historical Library edition of the Lincoln Bibliography contains a bit of its own history mystery. Its original owner was clearly a Lincolniana collector. He or she makes a note in the front about Benjamin P. Thomas’ Abraham Lincoln biography and then places a check mark next to every title that he or she had acquired, even handwriting acquired titles in locations where items were not included because they were too new. The result is a two volume acquisitions list. (My own acquisition list, in comparison, takes up a few stapled pages.) But who was the collector? We’re still trying to piece together the clues.

So, that’s a little of the history behind history. Next time someone begins talking about Abraham Lincoln, you can tell them about the Big Five and pull out the word Lincolniana.